MONUMENT 0.6: HETEROCHRONY (2019)

Strengthening the path she explores through her ›Monuments‹ series, Eszter Salamon creates on stage an imaginary field between the past and the present, bringing together traces of Sicilian musical archives and choreographed sensations inspired by the mummification rituals of the Capuchin Catacombs, in Palermo.

By juxtaposing our present time with traces of historical places and figures, the work takes a stand against oblivion by shaping memory through fiction. This choral piece imagines a continuum between life and death, the cohabitation of the living and the dead, and invents its own utopian body: a dancing and acoustic body.

Interview with Eszter Salamon by Bojana Cvejić

What does MONUMENT 0.6 commemorate? What’s behind the title “Heterochrony”?

I began thinking aboutthe question of how death is included in life when I visited the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo. From 1599, the monks of the Capuchin order have observed a peculiar custom: instead of burying their dead, they mummified them in this place, which is still open for visit. Later on, the custom spread to include wealthy citizens who paid to have the body of their loved ones preserved. In 1920, the last body joined a collection of about 1250 mummies. Since the modern times, death has been evacuated from our societies; the dead disappear from our view, their bodies are removed from the perception of the living. The encounter with the mummies of the Catacombs brought about a kinaesthetic shock for me. Getting so close to the appearance of the dead body I recalled the massive deaths of our times, genocide, carnage, but also sick bodies and illnesses like AIDS and cancer our society tends to hide and marginalize.

What does it mean to make a “monument” for you? This one is the sixth in a series.

The concept of “monument” is a bit of a bluff or a provocation. It is an exaggerated manner of naming power in the processes of memory and the writing of history. Who is the subject of history, who remembers and what is to be remembered. “Monument” means for me taking time to reflect on the pastin relation to our current times.

With your Monument series, are you seeking to redeem some parts of the past, those lost promises of the past that will flash up before our eyes in a moment of danger, to paraphrase Walter Benjamin?

I am interested in the histories that we tend to forget. Instead of a faithful revival and re-enactment, I search for transformation in which these histories could be linked with our present. For example, with MONUMENT 0.4: The Valeska Gert MonumentI sought out to construct the rest of Gert’s large oeuvre that remains unknown. The question that guided me was: what would that work be now if we could remember it at all, what would it look like and mean if it was staged today? In that sense, “heterochrony” is an apt term to describe what I try to do with each monument, juxtapose and superimpose different temporalities on stage to break out of the exclusivity of the present. I mount historically distinct times of past and present and sometimes also in a literal, physical sense, different ways that time passes for us on stage.

This is the fourth performance around death you made. Tales of the Bodiless (2011)in which I collaborated with you, begins with a description of a “bog body.”

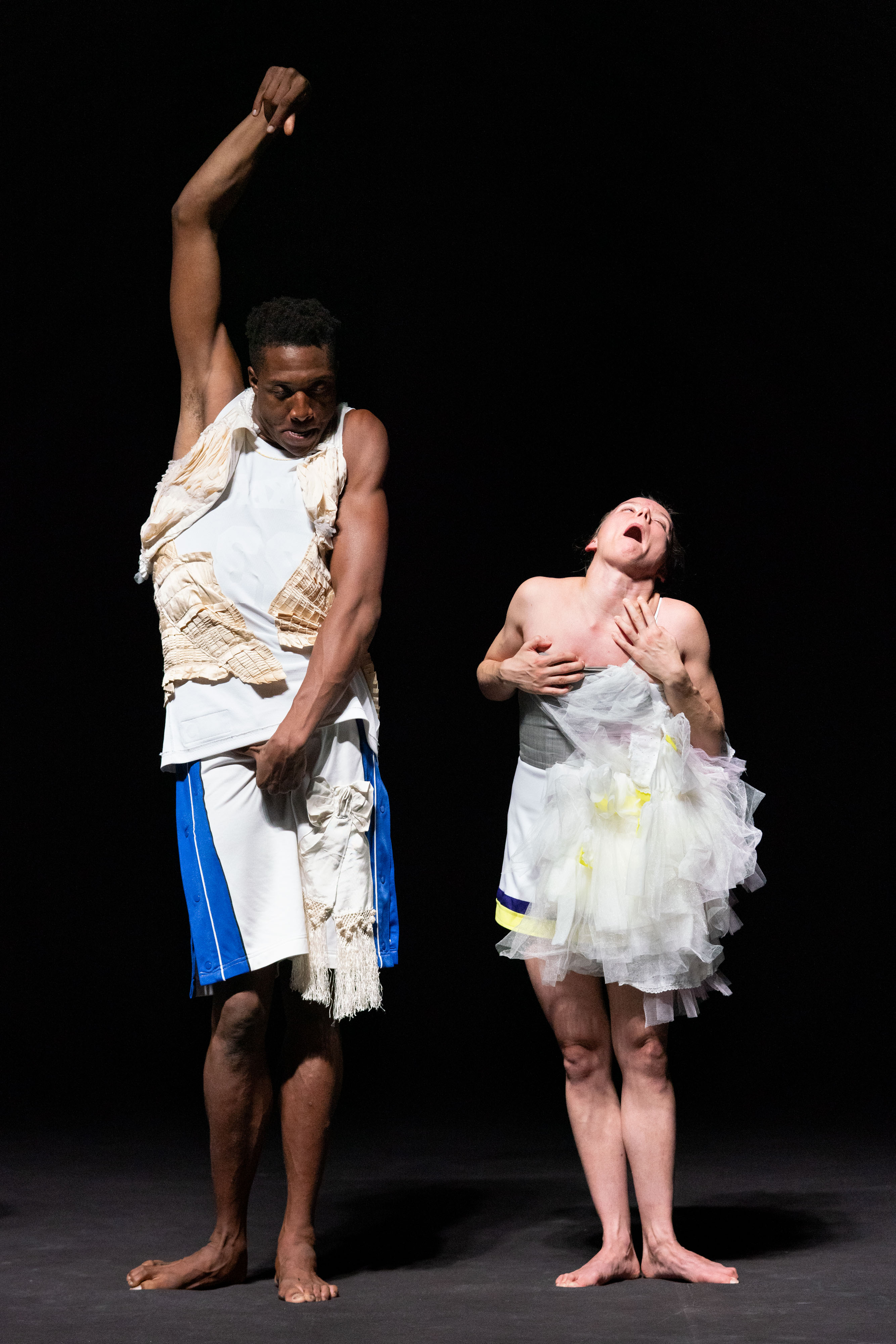

Yes. The way bodies are preserved in bogs, those special kinds of acid waters, is opposite of mummification. While the bones of the “bog body” are decalcified and organs and tissues are preserved for a very long time, mummies are skeletons with skin whose viscera are removed or emptied out. Mummies expose anatomy, bones that we feel but do not see. I wasn’t looking for embodying a mummy, but for relations that the dancers could draw from the mummy in their own bodies: figures, postures, petrified gestures, grimaces and rictus, that is the grin of the dead. We developed three techniques in shaping movement and presence. First, we applied a somatic approach to bones, skin, face and mouth in particular; this means that choreography is derived from sensations from within the internal space of the body, the experience that the dancers are ‘fictioning.’ Apart from somatic, that is physical fictions, the dancers use their imagination to produce personal fictions to accompany their movement. Their images are all different, and remain private, like tools that sustain attention and slow change. For example, they can include feigning the feeling of temperature, or invoking more synesthetic experiences where colors, rhythms, and sounds can merge. And the third and most important technique which I have developed in this piece, with the help of the vocal coach, Ignacio Jarquin, is centered on singing with the whole body. What if the entire body would act as the support, and sometimes also the source of sound, and not reduce singing to the vocal apparatus alone. Can the voice turn the body inside-out like a Moebius strip?

The mummy also brings the principle of distortion and deformation. You seem to pursue here, like in The Valeska Gert Monument, an interest for the grotesque.

This pursuit of the grotesque started out even earlier, in Dance #1, the duo I made with Christine De Smedt in 2008. In Dance #1, De Smedt and I ventured into a multiplicity of movement idioms and situations. Within this spectrum of exploration, we found grotesque expressions associated with the female body, as well as absurd humor. As the grotesque returns in my work, it begins to feature as a kind of resistance to the ideals of the neutral and universal body, in dissonance with the modern and contemporary dance’s seamless operations. Corpses are grotesque, they emanate pain, perhaps even torment in the moment of dying, and the rictus takes us to absurdity.

A great variety of songs in Italian and Sicilian language can be discerned in the musical landscape of this piece.

Sicily was at the crossroads of multiple occupations and invasions. Various conquerors and oppressors brought their cultural influences. Various cultures, Byzantine and the Moors left their imprint on the music I sought to explore through a journey from sacred pieces and folklore to opera; from the 12thcentury till the mid 19thcentury when Sicily was integrated into the unified state of Italy.

In one of your references to this piece, Michel Foucault’s lecture “The Utopian Body” (1966), the following reflection seems striking: “What is a mummy after all? The great utopian body that persists across time.”

The utopian body I have been looking forhere is one that can sing in immobility from the entire body, moving in such slowness that it gives itself the time not to be in the present only, but in the past and future of its fictions. For that we need to reinvent our means of expression and imagination. This is the case for the performers and it is also an invitation to the public

Concept, artistic direction and choreography Eszter Salamon Choreography and performance Matteo Bambi, Mario Barrantes Espinoza, Krisztiàn Gergye, Domokos Kovàcs, Csilla Nagy, Olivier Normand, Ayşe Orhon, Corey Scott-Gilbert, Jessica Simet Text Eszter Salamon, Elodie Perrin, Poem Paul Eluard Musical research Eszter Salamon, Johanna Peine Vocal coach Johanna Peine, Ignacio Jarquin Musical direction and arrangements Ignacio Jarquin Dramaturgical advisor Bojana Cvejić Rehearsal assistant Christine De Smedt Light design Sylvie Garot Sound Marius Kirch, Felicitas Heck Costume Design Flavin Blanka Technical Direction Matteo Bambi Production Botschaft GbR/ Alexandra Wellensiek, Studio E.S/ Elodie Perrin

Coproduction PACT Zollverein (Essen), Théâtre Nanterre-Amandiers (Nanterre), HAU Hebbel am Ufer (Berlin), KunstFestspiele Herrenhausen (Hannover), Wiener Festwochen (Vienna), CCN de Caen en Normandie in the frame of accueil studio With the support of Kunstencentrum BUDA (Kortrijk), de O Espaço do Tempo (Montemor-o-Novo) Funded by the Regional Directory of Cultural Affairs of Paris – Ministry of Culture and Communication, the region Île-de-France and the German Federal Cultural Foundation

Thanks to: Odile Blanchard, Fanny Bouquerel, Luca Camilletti, Margit Koch, Camille Lugnier, Leonor Lopes, Marie Maresca, Elena Martin, Matthias Mohr, Christophe Poux, Sabina Stücker, Asphalt Festival / Christof Seeger-Zurmühlen und Jacqueline Friedrich, dem Théâtre de l’Odeon und dem Team von Nanterre-Amandiers

Music based on the excerpts from songs and compositions 12th-19th century:

“C’erano tre sorelle” folk song from 12th-13th century, arrangement for eight voices by Ignacio Jarquin

“'Dolente Immagine di Fille mia” arietta by Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835)

“'Tarantella del Gargano” traditional love song from the region of Foggia

“Tenebrae factae sunt” (1611) excerpt from Responsories for Holy Week by Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa (1566-1613) arrangement for five voices by Ignacio Jarquin

“La Giuditta dormi” from the oratorium Giuditta (1690) by Alessandro Scarlatti (1660 – 1725)

La Surfurara, the sulfur miner’s song, anonymous

Canto dei Carrittieri Siciliani, anonymous

Ninna nanna ri la rosa, traditional Sicilian lullaby

“Montedoro” introduction from Troparium di Catania 12th century, sung by people in the church

![]()

![]()

Strengthening the path she explores through her ›Monuments‹ series, Eszter Salamon creates on stage an imaginary field between the past and the present, bringing together traces of Sicilian musical archives and choreographed sensations inspired by the mummification rituals of the Capuchin Catacombs, in Palermo.

By juxtaposing our present time with traces of historical places and figures, the work takes a stand against oblivion by shaping memory through fiction. This choral piece imagines a continuum between life and death, the cohabitation of the living and the dead, and invents its own utopian body: a dancing and acoustic body.

Interview with Eszter Salamon by Bojana Cvejić

What does MONUMENT 0.6 commemorate? What’s behind the title “Heterochrony”?

I began thinking aboutthe question of how death is included in life when I visited the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo. From 1599, the monks of the Capuchin order have observed a peculiar custom: instead of burying their dead, they mummified them in this place, which is still open for visit. Later on, the custom spread to include wealthy citizens who paid to have the body of their loved ones preserved. In 1920, the last body joined a collection of about 1250 mummies. Since the modern times, death has been evacuated from our societies; the dead disappear from our view, their bodies are removed from the perception of the living. The encounter with the mummies of the Catacombs brought about a kinaesthetic shock for me. Getting so close to the appearance of the dead body I recalled the massive deaths of our times, genocide, carnage, but also sick bodies and illnesses like AIDS and cancer our society tends to hide and marginalize.

What does it mean to make a “monument” for you? This one is the sixth in a series.

The concept of “monument” is a bit of a bluff or a provocation. It is an exaggerated manner of naming power in the processes of memory and the writing of history. Who is the subject of history, who remembers and what is to be remembered. “Monument” means for me taking time to reflect on the pastin relation to our current times.

With your Monument series, are you seeking to redeem some parts of the past, those lost promises of the past that will flash up before our eyes in a moment of danger, to paraphrase Walter Benjamin?

I am interested in the histories that we tend to forget. Instead of a faithful revival and re-enactment, I search for transformation in which these histories could be linked with our present. For example, with MONUMENT 0.4: The Valeska Gert MonumentI sought out to construct the rest of Gert’s large oeuvre that remains unknown. The question that guided me was: what would that work be now if we could remember it at all, what would it look like and mean if it was staged today? In that sense, “heterochrony” is an apt term to describe what I try to do with each monument, juxtapose and superimpose different temporalities on stage to break out of the exclusivity of the present. I mount historically distinct times of past and present and sometimes also in a literal, physical sense, different ways that time passes for us on stage.

This is the fourth performance around death you made. Tales of the Bodiless (2011)in which I collaborated with you, begins with a description of a “bog body.”

Yes. The way bodies are preserved in bogs, those special kinds of acid waters, is opposite of mummification. While the bones of the “bog body” are decalcified and organs and tissues are preserved for a very long time, mummies are skeletons with skin whose viscera are removed or emptied out. Mummies expose anatomy, bones that we feel but do not see. I wasn’t looking for embodying a mummy, but for relations that the dancers could draw from the mummy in their own bodies: figures, postures, petrified gestures, grimaces and rictus, that is the grin of the dead. We developed three techniques in shaping movement and presence. First, we applied a somatic approach to bones, skin, face and mouth in particular; this means that choreography is derived from sensations from within the internal space of the body, the experience that the dancers are ‘fictioning.’ Apart from somatic, that is physical fictions, the dancers use their imagination to produce personal fictions to accompany their movement. Their images are all different, and remain private, like tools that sustain attention and slow change. For example, they can include feigning the feeling of temperature, or invoking more synesthetic experiences where colors, rhythms, and sounds can merge. And the third and most important technique which I have developed in this piece, with the help of the vocal coach, Ignacio Jarquin, is centered on singing with the whole body. What if the entire body would act as the support, and sometimes also the source of sound, and not reduce singing to the vocal apparatus alone. Can the voice turn the body inside-out like a Moebius strip?

The mummy also brings the principle of distortion and deformation. You seem to pursue here, like in The Valeska Gert Monument, an interest for the grotesque.

This pursuit of the grotesque started out even earlier, in Dance #1, the duo I made with Christine De Smedt in 2008. In Dance #1, De Smedt and I ventured into a multiplicity of movement idioms and situations. Within this spectrum of exploration, we found grotesque expressions associated with the female body, as well as absurd humor. As the grotesque returns in my work, it begins to feature as a kind of resistance to the ideals of the neutral and universal body, in dissonance with the modern and contemporary dance’s seamless operations. Corpses are grotesque, they emanate pain, perhaps even torment in the moment of dying, and the rictus takes us to absurdity.

A great variety of songs in Italian and Sicilian language can be discerned in the musical landscape of this piece.

Sicily was at the crossroads of multiple occupations and invasions. Various conquerors and oppressors brought their cultural influences. Various cultures, Byzantine and the Moors left their imprint on the music I sought to explore through a journey from sacred pieces and folklore to opera; from the 12thcentury till the mid 19thcentury when Sicily was integrated into the unified state of Italy.

In one of your references to this piece, Michel Foucault’s lecture “The Utopian Body” (1966), the following reflection seems striking: “What is a mummy after all? The great utopian body that persists across time.”

The utopian body I have been looking forhere is one that can sing in immobility from the entire body, moving in such slowness that it gives itself the time not to be in the present only, but in the past and future of its fictions. For that we need to reinvent our means of expression and imagination. This is the case for the performers and it is also an invitation to the public

Concept, artistic direction and choreography Eszter Salamon Choreography and performance Matteo Bambi, Mario Barrantes Espinoza, Krisztiàn Gergye, Domokos Kovàcs, Csilla Nagy, Olivier Normand, Ayşe Orhon, Corey Scott-Gilbert, Jessica Simet Text Eszter Salamon, Elodie Perrin, Poem Paul Eluard Musical research Eszter Salamon, Johanna Peine Vocal coach Johanna Peine, Ignacio Jarquin Musical direction and arrangements Ignacio Jarquin Dramaturgical advisor Bojana Cvejić Rehearsal assistant Christine De Smedt Light design Sylvie Garot Sound Marius Kirch, Felicitas Heck Costume Design Flavin Blanka Technical Direction Matteo Bambi Production Botschaft GbR/ Alexandra Wellensiek, Studio E.S/ Elodie Perrin

Coproduction PACT Zollverein (Essen), Théâtre Nanterre-Amandiers (Nanterre), HAU Hebbel am Ufer (Berlin), KunstFestspiele Herrenhausen (Hannover), Wiener Festwochen (Vienna), CCN de Caen en Normandie in the frame of accueil studio With the support of Kunstencentrum BUDA (Kortrijk), de O Espaço do Tempo (Montemor-o-Novo) Funded by the Regional Directory of Cultural Affairs of Paris – Ministry of Culture and Communication, the region Île-de-France and the German Federal Cultural Foundation

Thanks to: Odile Blanchard, Fanny Bouquerel, Luca Camilletti, Margit Koch, Camille Lugnier, Leonor Lopes, Marie Maresca, Elena Martin, Matthias Mohr, Christophe Poux, Sabina Stücker, Asphalt Festival / Christof Seeger-Zurmühlen und Jacqueline Friedrich, dem Théâtre de l’Odeon und dem Team von Nanterre-Amandiers

Music based on the excerpts from songs and compositions 12th-19th century:

“C’erano tre sorelle” folk song from 12th-13th century, arrangement for eight voices by Ignacio Jarquin

“'Dolente Immagine di Fille mia” arietta by Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835)

“'Tarantella del Gargano” traditional love song from the region of Foggia

“Tenebrae factae sunt” (1611) excerpt from Responsories for Holy Week by Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa (1566-1613) arrangement for five voices by Ignacio Jarquin

“La Giuditta dormi” from the oratorium Giuditta (1690) by Alessandro Scarlatti (1660 – 1725)

La Surfurara, the sulfur miner’s song, anonymous

Canto dei Carrittieri Siciliani, anonymous

Ninna nanna ri la rosa, traditional Sicilian lullaby

“Montedoro” introduction from Troparium di Catania 12th century, sung by people in the church